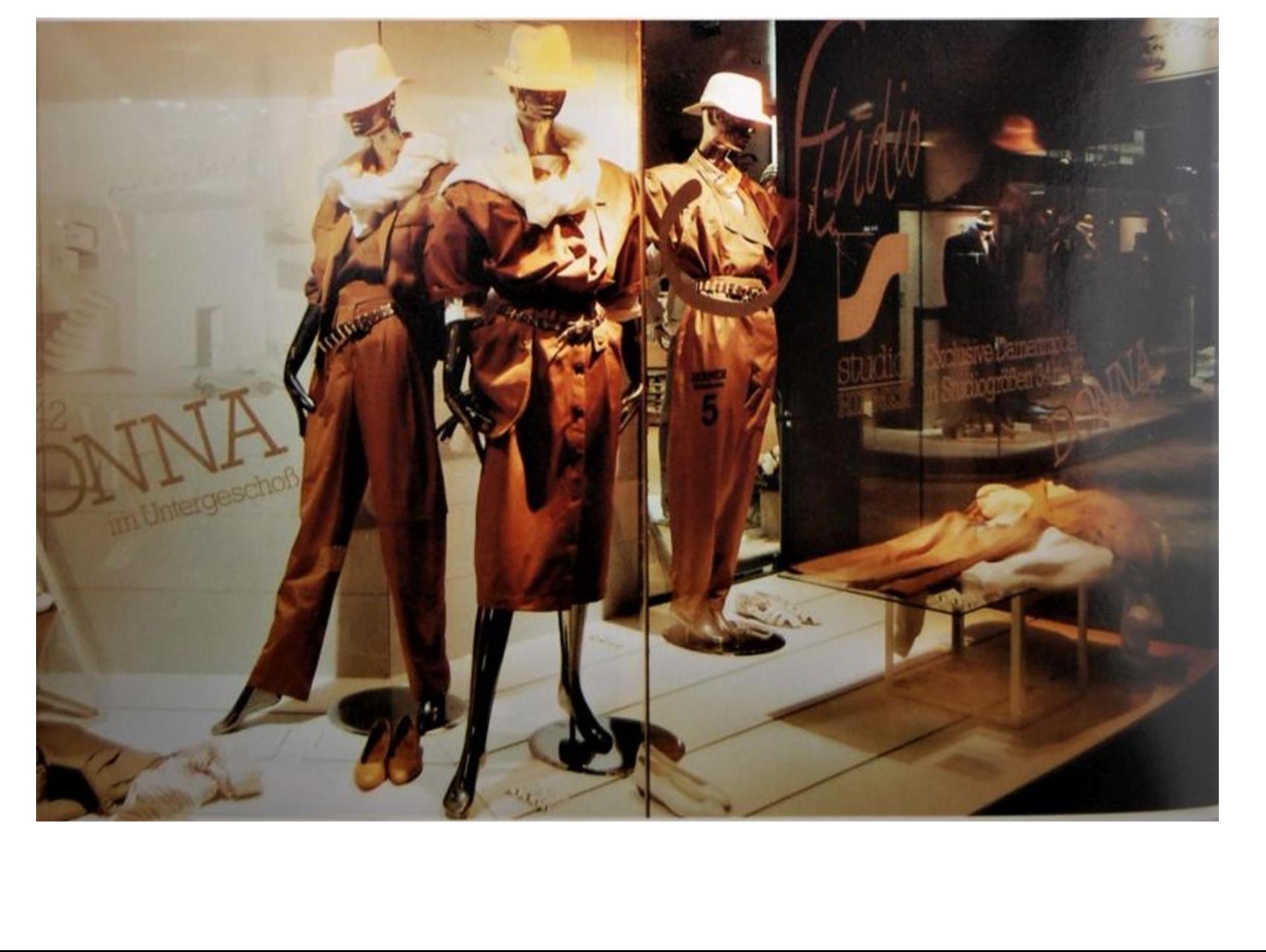

Display Mannequins

What is it that fascinates us about our artificial counterparts, which are actually not counterparts? And why are female mannequins basically unnaturally designed? Often in discriminatory poses and in a sexist context. Fortunately, we no longer live in the fifties, sixties or seventies, where advertising was sexistly created, but if you look at the female mannequins today, you ask yourself, especially as a woman, who served as an example to the sculptors. Aliens?

The window mannequin - Galatea of modernity

‘’The doll has played a fairly large role in human life, and has been since times. Not just as a symbol or fetish. However, the term "doll" also means rigid, immovable. The insect that has solidified into a mutation or transformation is also called a pupa. On the other hand, you "let the dolls dance" when you get something going, when you want to bring life to the booth.’’ (The shop window 05/1979: 30)

In a textbook for the trainee designer for visual marketing, the mannequin is described as follows:

‘’Full figures, half figures and parts of figures (e.g. arms, stockings) are necessary for the appropriate presentation of clothing. They are either made naturalistic based on a living model or given an abstract look. Which shape you prefer depends on the prevailing fashion. Naturalistic-realistic figures have an almost living appearance, which the sculptor tries to achieve by reproducing posture and facial expression. There are standing, striding, sitting and lying figures, with arms raised, lowered or bent, legs spread or crossed. Today they are designed in such a way that they can be easily put on despite their posture: both arms can be unhooked, the upper and lower part are coupled below the waist (important for bathing clothes), one leg can be unhooked. Shoes are no longer modeled, but put on. ‚‘(Waschner 1986: 148)

For professionals, it is an everyday workpiece for product advertising, which is not subject to a transfigured concept, like some enthusiasts or collectors. For us who use this work tool for professional purposes, the gender of the figure is only relevant at first, whether it is women's or men's clothing that is to be put on. No textbook says that the female window mannequin associates more than wearing clothes, but results from her holistic use.

The complexity of the (female) mannequin was already recognized by Surrealist artists and made it the main attraction of an exhibition. The surrealists who launched the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris in 1938 had a special interest in female window mannequins, which was based on the actual use of the figures. On the one hand, the use of women as a sexual object was emphasized, and on the other hand, with this industrial "woman" product, the surrealists showed how much the "capitalist culture of use" had taken up public space. With the "erotic economy" of the figures, which was kept quietly in society, the artists were able to show what the purpose of the figures in the shop window was. The basis was the identification with the highly stylized perfection of the female figure and the advertised, inaccessible products behind glass, which should arouse desire. This was exaggerated with the surrealistic alienation of the figures and critically demonstrated (see Filipovic 1999: 208f). Nothing has changed in this highly stylized perfection. Katharina Sykora describes the window mannequin as a seducer who offers her availability for money in the "threshold area of the window" and thus becomes a product herself (cf. Sykora 2002: 130). It puts passers-by into a frenzy, triggered by their unattainable beauty and a femininity that does not seem to be out of this world:

This attraction of these artificial seducers is evoked in countless feature pages, essays and novels of the time. It owes its existence to an illusionistic closeness to reality that ties the dolls back to their role model, the real woman. Because the window mannequins are confusingly similar to their doppelgangers on the street. (Sykora 2002: 130)

It doesn't stop there. The copy in the shop window becomes the identity-creating example of a society that is looking for ideals, even if they are only visual in nature. The fascination that comes from mannequins is not a phenomenon of the modern age, but is to be found in the fact that man has had the desire since ancient times to create a surrogate of his kind. And in the beginning there was the doll.

Unlike sculptures, dolls are subjected to arbitrary treatment. Be it tenderness or the use of force - as a substitute for a missing human body, they are at the mercy of what people imagine and want to implement. Cult rituals and sexual acts have a long tradition of using dolls. Pygmalion is a role model for men who are always at the service of a compliant art woman (cf.Lüdeking 1999: 220). They can be seen in the shop window, the art women, the “ideal pictures” of women, created as their creator imagines them and staged in the shop window in such a way that the pictures that are staged there put the figure's body in a new context put. On the one hand there is the figure with her body, which is already enough statement in the modeled pose. On the other hand, this expressive body is combined with other bodies, objects and shop window symmetries in such a way that the reading of the body enhances reverses or abstracts its meaningfulness.

Decorative cosmetics, costumes, shows - all of this helps to deceive and confuse us in our discovery phase. And at an ever faster pace. Extreme images of the body in the media almost demand that our bodies adapt to this pace of modeling. Lüdeking goes even further and compares the portrayal of a virtual dream woman and her emergence in the novel Idoru by William Gibson with the collective of countless wishes that are placed on today's »ideal woman« far from the virtual and literary world. The dream woman in the novel is a conglomerate of tendentious desires that are constantly recalculated and combined. The artificial end product reveals itself above all as a hologram charged with sexual energy. The difference to the real world is hardly noticeable, since nobody is able to understand or even control these independent processes of shaping our ideal images. Lüdeking does this, among other things. to the "fetishistic veneration of the dreamy and untouchable" mannequins that has been observed since the beginning of the last century. A "data compression of a time-lapse film" could illustrate the modification to which the ideal images of female beauty, i.e. beauty queens, mannequins or models, have been subjected over time (cf. Lüdeking 1999: 225f). The female mannequin is an example of this development, which was somewhat slower but all the more extreme. The women in the shop windows became slimmer over time. In the 1950s, oversized women's bodies were also visible in the shop windows, until the »Twiggy« model appeared in the 1960s and the »androgynous nanny« determined the image of women.

The figures did not get thicker again in the coming decades. They grew in height to a model size common at the time and the shoulder blades and hip bones were modeled out so that they looked even leaner. Only the real woman gained body.

However, it is undesirable for customers that the window mannequin "grows with the child". They want an ideal picture with which they can identify and the manufacturers of the figures adapt. Also in the interests of retailers who cannot afford to leave the goods behind because customers feel put off by a real picture of themselves (cf. Szymkowiak 2007: 35). The shop window also claims that "the customer can easily identify with the lifelike mannequins today" (see The Shop Window 05/1979: 30). The window mannequins are made based on real models from the fashion industry or fashion photography. The fashion photography captivates with the poses of the models and their staging. Experts see the poses of the mannequins as an important stylistic device to communicate with the viewer:

It is therefore necessary to deal professionally with a visual and symbolic language that conveys messages of values that are at least unconsciously perceived by consumers. The trump card of modern display mannequins is the power of the pose. Because ultimately, in the design of the figures, insights into the power of human body language are expressed. Posture, gestures and facial expressions are crucial in all interpersonal encounters for the first impression, i.e. for sympathy, interest, curiosity and the willingness to enter into a dialogue. This is exactly the starting point when using figures as a replica of human bodies. They always embody a message and stand for the offer of the fashion trade to enter into dialogue with the consumers. From the perspective of marketing experts, this is a particularly valuable commodity. Because: Dialogue means pure emotion. (Reiferscheid 2007: 127)

The window mannequin is therefore an important medium when it comes to the model of an idealized body image. Because they are not just "clothes racks" that represent the value of the goods, but have grown to an independent value that is closely observed by those looking for identity:

The moving in of the mannequin was functional. Instead of the human body itself, the goods (clothes, jewelry, bags, etc.) were hung on wooden figures, which mostly had ideal figures and faces. So in the beginning, in the 19th century, the mannequins were just body stands and means of the etalage, i.e. Devices for hanging goods soon received [...] more and more independent value. They not only exhibited more goods, but also themselves. Therefore, the mannequins became ever finer and more refined in their design, more and more human-like. Soon they no longer only showed the ideal body, but also the ideal posture, fashionable poses, the ideal mood, the spirit of the times. This symbolic function of the mannequin was particularly discovered by the surrealists and used artistically. Since then, the mannequin has played a major role in the fine arts that are still waiting for their historian, but to which we would like to refer with a few examples (from Dali’s drawer body to Meret Oppenheim to Cocteau). Of course there are interdependencies, since the magazines of the window decorators report on the development of art. It seems to me of fundamental importance, however, that the shop window mannequin and its symbolic-cultural meaning have been almost invisibly integrated into the language of art as formal parameters, as design and expression elements. (Weibel 1979: 15)

The interactions mentioned arise not only from the editorial art contributions in the specialist journals, but art historical aspects are and have always been an integral part of the curriculum of trainees for designers in visual marketing. References to art historical conditions are essential for an attractive shop window design and are even desirable, in terms of aesthetics. If the first expenses arose at the beginning of the last century under artistic guidance or were designed by artists themselves, the job description changed over the years and after the Second World War resulted in a retail-controlled and sales-oriented apprenticeship. As already mentioned, the use of the window mannequins takes place under factual arguments and in the manageable number of textbooks of the trade one searches in vain for the mentioned attributes of the "seductive and manipulative" female figure. The designers for visual marketing use them for product presentation and above all they are staged. Female figures in a "feminine" environment and male figures in a "masculine" environment. Advertisers, in this case advertisers, use gender stereotypes to underline the message of their designs, often in an exaggerated and deliberately exaggerated form. Getting the attention of passers-by according to the AIDA formula is paramount! The body language of the characters and the context in which they are placed play a major role. The shop window serves as the stage for a cliché theater that plays the sexes against one another. The basis of this research work is on what basis this happens and which development has been associated. Gender stereotypes are still an issue in the advertising industry. In the 1950s, women were housewives and mothers, men were the head and breadwinner of the family, which was clearly propagated in advertising, but despite the development of new images of women, the advertising industry found it difficult to refrain from this role performance. Men and women still play their roles in advertising, albeit in a slightly different form. Women as child-loving mothers who prepare delicious meals for their husbands, women who are only shown in care professions, commercials with "women's interests" such as diets, cosmetics, family and fashion. And women as objects that are placed next to the same for a wide variety of products, mostly undressed. With the increasing sexualization of advertising in the 1970s, which continued to increase as a result of sexual liberalization, criticism from feminists grew.

They accused men of taking advantage of the breakdown of sexual taboos and conservative values in order to manifest their claim to rule over women. The major criminal law reform generously dealt with pornographic content in the media and the advertising missed no opportunity to celebrate great success with the "sex wave". Too lightly, one could still see the need for this to be satisfied visually by the long taboo of sexual pleasure, but the drastic depictions of pornographic images and the accompanying objectification of women, which was carried over into everyday female life, were formulated by feminist criticism , Women, in particular, suffer from this "drive model of the sexes in the capitalist exploitation process", since they are degraded to an object that has to be available to specifically male needs (cf. Gorsen 1987: 157). Naomi Wolf defines the "survival of consumer culture", which "prevents gender communication" and "sexual insecurity". "Sexually cloned beings" support this market, which consists of "men who want objects and women who want to be objects" (Wolf 1990: 199).

In the past 13 years alone, the German Advertising Council has issued over 120 (werberat.de: 2018) public complaints. This problem of the discriminatory display of women from a sexual point of view can no longer be observed in shop windows. But the "pictures of women" in advertising, in this case in advertising, still look fundamentally different from "pictures of men".